The Dragon's Mandate: From Celestial Deity to Symbol of Personal Sovereignty in Jewelry

In the collective imagination of the West, the dragon is a creature of hoarded gold and fiery destruction, a beast to be slain by a knightly hero. This image, however, is a profound misrepresentation when gazing eastward. Across China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, the dragon soars not as a monster, but as a deity—a benevolent, powerful, and essential force governing the natural and cosmic order. Its journey from a primal symbol of nature's fury to the exclusive emblem of the Son of Heaven, and finally to a modern token of personal empowerment, is a narrative that mirrors humanity's own evolving relationship with power, authority, and the self.

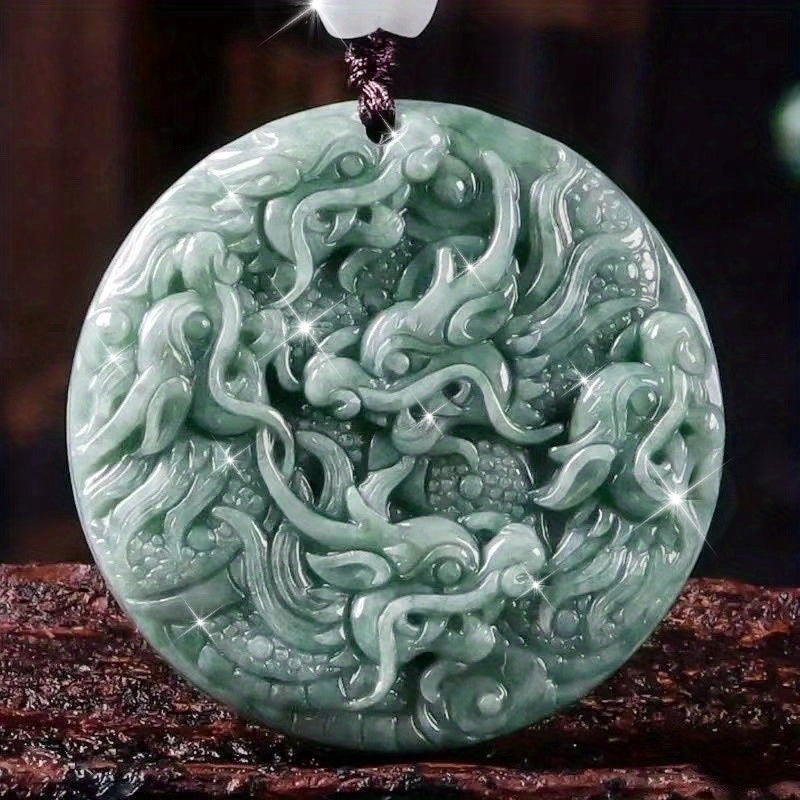

The intricate hand-carving on the Dragon Guardian pendant captures the traditional representation of powerful, imbricated scales.

View the Jewelry Piece →I. Primal Origins: The Dragon as Explanation and Elemental Force

Long before it adorned imperial robes, the dragon was born from necessity. Neolithic communities living at the mercy of monsoons, floods, and earthquakes sought to personify these awesome, life-giving and life-taking forces. The earliest dragon-like motifs found on Chinese pottery (c. 4000 BCE) are serpentine, water-associated creatures. Scholars like sinologist Sarah Allan suggest that the Chinese dragon originated as a representation of the thunderstorm—the coiling body as the storm cloud, the scales as the glint of rain, the roar as thunder. It was not a god to be worshipped in a temple, but a force to be acknowledged, appeased, and understood.

This primal dragon was an amalgam, a composite creature reflecting a holistic view of nature's power. Its antlers hinted at the stag's connection to the forest, its scales mirrored the protective armor of the fish (and later, the carp's legendary perseverance), its claws showed the eagle's dominion over the sky, and its sinuous body echoed the serpent's earthly wisdom. It was a creature of all domains: earth, water, and sky. This inherent multiplicity made it the perfect symbol for a force that could bring nourishing rain or devastating flood—a force that was itself a negotiation of opposites.

II. Systematization: The Dragon Enters the Bureaucracy of Heaven

As Chinese civilization consolidated under dynastic rule, the chaotic, primal force of the dragon needed to be integrated into a structured worldview. The concept of the "Mandate of Heaven" (天命 Tiānmìng)—the divine right to rule—required a celestial intermediary. The dragon was perfect for this role. It became the symbol of the emperor, the one man on earth who could mediate between the heavenly order and the human realm.

This was not merely an aesthetic choice; it was a political and cosmological one. The dragon's image was codified and regulated with astonishing precision during imperial times. The five-clawed dragon (龙 lóng) was reserved exclusively for the emperor. Princes and high nobility could use a four-clawed mang (蟒), and officials of lower rank might use a three-clawed creature. To misappropriate the five-clawed dragon was not just a fashion faux pas; it was treason, a challenge to the cosmic order itself.

The imperial dragon was no longer just a force of nature. It was now an administrator. Different colored dragons governed different directions and seasons. The Azure Dragon of the East governed spring. The imperial Yellow Dragon (associated with the center and the emperor) represented the earth element and supreme sovereignty. The dragon was woven into the very fabric of state ritual, architecture (dragon pillars, dragon thrones), and cosmology. It had become the ultimate brand of legitimate, heaven-sanctioned authority.

VI. The Personal Sovereign: Wearing the Dragon Today

In the contemporary world, the idea of a single, heaven-mandated ruler is obsolete. Yet, the human need for sovereignty—for agency, self-command, and the authority to shape one's own life—is more acute than ever. We navigate a world of fragmented attention, external demands, and often diffuse personal power. This is where the dragon symbol undergoes its most fascinating modern transformation.

To wear a dragon today is not to aspire to an imperial throne, but to reclaim a personal mandate. It is an assertion of inner authority. The dragon pendant resting against one's chest becomes a tactile reminder: You are the sovereign of your inner realm. You command your attention, your values, your responses. It symbolizes the strength to set boundaries (the dragon's impenetrable scales), the wisdom to navigate complexity (its serpentine adaptability), and the power to manifest change (its command of rain and creative force).

This reinterpretation is deeply respectful of the symbol's history. It does not diminish the dragon's power but redirects it inward. It democratizes the Mandate of Heaven, suggesting that each individual has a divine right to self-governance and personal fulfillment. The "protection" it offers is not just from external harm, but from internal dissipation—from the erosion of will, the loss of focus, and the surrender of personal agency.

A modern interpretation of sovereign power: the dragon as a companion for personal resolve and inner command.

View the Jewelry Piece →Closing Reflection: The dragon's journey is a mirror. It reflects humanity's progression from fearing raw nature, to systematizing power in a celestial monarchy, to ultimately seeking that power within the individual self. A piece of dragon jewelry, therefore, is more than an ornament. It is a conversation with history, a connection to a profound archetype, and a quiet, daily declaration. It is the assumption of a personal mandate—not to rule others, but to master the intricate, wonderful, and challenging kingdom of one's own life. In a world that constantly asks us to comply, to consume, and to conform, the dragon whispers a different, older truth: you have the right to command your own story.